Wooster Publicans in Buckinghamshire - Part 1

Wooster Publicans in Buckinghamshire - Part 1This free script provided by JavaScript Kit

© The Wooster Family Group

Wooster Publicans in Buckinghamshire - Part 1 By Cindy MillerA good local pub has much in common with a church, except that a pub is warmer and there's more conversation. --- William Blake As an American, I grew up hearing my father, James Miller (I14) tell stories about spending his Army furlough at the end of World War II in England and how his Wooster cousins, including his "Aunt Edie" (Edith Wooster Goff, I00953) and her daughter Eva warmly welcomed him into their home, served him tea in bed every morning, and entertained him with nightly trips to their local pub.1 His mother, Lillie Wooster Miller (I02945), had immigrated to the United States in 1902 along with her parents, Joseph (I00948) and Hannah North Wooster (I00950) and several other family members. They settled in the west Georgia crossroads community of Wooster, named after Joseph's younger brother George (I02649) who had come there in 1872, so I always wanted to know more about our family's ties to their homeland. When I visited England in 1991, I was thrilled to discover that my great-great grandfather Joseph Wooster had been a publican at the Star in Princes Risborough. I developed an idealized image of him being a beloved pillar of the community, hosting his neighbors at his pub and making life better for his friends and patrons, and I was eager to learn more about his life. I'd even heard from my dad's siblings and cousin that my grandmother Lillie had been born in a pub. When research via the internet became possible and I could do genealogy as a hobby, I gradually learned more about Joseph and other Wooster family members in Buckinghamshire in the vicinity of Princes Risborough, and I began noticing a curious trend - there were other pub operators among my 19th century ancestors. Not just one or two, but multi-generational lines of them among several family groups in the county! I decided to try a systematic search of Wooster publicans and was stunned to find even more as I branched out beyond my immediate family lineage. Using the Wooster Family Group website along with Ancestry sources, I've come to believe that if you shake a branch of the tree, a surprising number of publicans, victuallers and beer retailers will fall into view. My premise is that there were lots of Woosters, lots of public houses, so therefore lots of Wooster publicans! It's likely that we all have some to discover. In this article, I'll introduce you to my rough and tumble Wooster ancestors in Bucks who primarily made their living farming and selling beer in rural villages in the mid to late 1800's and early 1900s. Because I've identified more than a dozen other Woosters who were in the business in the Home Counties and London, I hope to highlight their lives in subsequent newsletter articles so that others might find their unknown publican ancestors. Their stories can help us better understand what life was like for Woosters during the late Victorian and early pre-World War II era. Origins of Alehouses, Public Houses, and Beerhouses in Britain First, it's helpful to know about the types of drinking establishments and how they evolved in the 1800s. Long before the development of public houses, ale had existed in Britain for many centuries as a commodity made in the home for family consumption. Brewed from only barley, yeast and water, it was much safer to drink than ordinary water because of its boiled processing. Drinking ale was also a way to add calories and nutrients for those who had meagre diets. Sweeter, stronger and darker than modern-day ales, the earlier product quickly spoiled and was normally drank in or very near the place it was made. Women known as "alewives" brewed it for their families, and any surplus could be sold to neighbors who could not produce their own.2 This process evolved into the establishment known as an alehouse.3 In the early 1400s, hops were introduced into Britain from continental Europe, and the new product called beer became common, displacing traditional ales because of the preservative effects of the hops. Beer could be casked and transported to locations well beyond its production site, or stockpiled for consumers who could buy it from families who made and kept it for sale on their premises.4 Public houses, or "pubs," originally referred to small drinking places established in private homes that exclusively sold beer and sometimes food. As these expanded in popularity in the 18th century, they quickly became a specialty niche between beerhouses (private homes whose residents sold beer on and off site) and the larger taverns and inns that had long served travelers with food, stables and overnight accommodations. By the 19th century, the term pub gradually expanded in meaning to include most all beerhouses, taverns and inns.5 Commercial breweries first opened in London in the 1600s, and these businesses gradually expanded into smaller cities and towns over the next two centuries, providing beer to the growing numbers of pubs and ending most home brewing.6 By the 1700s, beer consumption declined due to the rise of distilled spirits such as gin in Britain, and these products caused an unprecedented rise in drunkenness, especially in larger cities where "ginhouses" flourished. This set the stage for a new sequence of regulations in the 1800s that would encourage the spread of licensed beer drinking places to counter liquor consumption and make beer once again the preferred drink of the working class. The Beerhouse Act of 1830 enabled anyone to buy a licence, without the normal oversight from local magistrates, for the affordable cost of two guineas, or approximately 50 shillings.7 At this point, the number of beer retailers, beerhouses and public houses increased dramatically, and set the stage for our mid-19th century Woosters to enter the business.8 From the 1841 Census onward, residents who sold beer generally were described in the records as either "publicans" (if they held a licence to operate a "signed" house for the public, meaning it had a painted image over its door to signify its unique name to illiterate community members}, or as "beer retailers" if they served beer from taprooms in their homes,9 or sold beer off-site for consumption in others' homes. The legal term "licensed victualler" appears for those who operated pubs and also sold food and meals with the beer.10 All three categories of operators had to acquire licences from local authorities to run their businesses. Publicans and victuallers were also commonly identified in the censuses by the names of their establishments, allowing researchers to link their ancestors to specific buildings that may still exist. Most publicans leased these premises from landholders or, more commonly by the later 1800s, from breweries that bought the structures. These pubs became known as "tied houses" that sold beer on agreement from one specific brewery.11 The overwhelming success of the Beerhouse Act of 1830 caused another rise in public drunkenness. This led to the Beer Act of 1869 that reinstated the local magistrates' control of the licensing process. They could deny new or remove existing licences from publicans and beer retailers who were suspected of breaking regulations and contributing to bad behavior in the community. The growing influence of the temperance movement also prompted magistrates to reduce the numbers of pubs and beerhouses and curb rising rates of alcoholism. Public house researcher Simon Fowler estimates that by 1870, up to a quarter of working-class family budgets were spent on beer, "causing great misery and ruin for many."12 Similarly, a report from a Church of England temperance committee reported in 1869 that in communities that have no beerhouses and pubs, "the absence of crime, the sobriety and order of those parishes is most striking."13 The highest number of licence holders peaked between 1871 and 1891, with more than 100,000 in England and Wales. During this time, it's estimated that there was approximately one pub per 250 persons.14 The Bucks Woosters of the mid-to-late Victorian era entered these professions in sizable numbers judging from those identified in this project. We can assume that the economic depression that deeply affected rural life during this time was a significant reason for the increase in licences as farmers and other stressed tradesmen hoped to supplement their incomes with beer sales. Imports of cheap grain from the U.S. and Canada brought market prices to historic lows in Britain and led to migration away from farming communities just at the time new beer retailers and publicans needed customers. With this context in mind, we can better understand the financial stresses our Wooster ancestors likely faced in Bucks at the time. Simon Fowler identified four common trends in the pub business and these proved to be true for our beer-selling relatives: (1) they often involved middle-aged or elderly persons who were retired or otherwise unable to work in their communities; (2) publicans and beer retailers commonly operated these business as a part-time venture to supplement their trades or farming occupations; (3) they often involved entire families with children who had roles such as taproom servers or cooks; and (4) wives often took over licences from their deceased husbands, enabling widows to earn a living for themselves and their children.15 We'll see all of these patterns in our Wooster members featured in this article. Caleb North (1823-1885) - Towersey, Bucks To understand how Joseph Wooster came into the pub business, it's necessary to meet his in-laws, Caleb and Ann Monger North who lived in the village of Towersey, located about seven miles west of Princes Risborough, or nine miles southwest of Aylesbury. Caleb grew up as a farmer's son in this community of about 450 residents, but by age 24 in 1847, he had married Ann and was listed as a publican in the parish births and christening book.16 In the 1851 Census, he was described as the publican living at a building named the Brick Kiln, and in a 1853 directory he was simply listed as a beer retailer, suggesting that he was selling beer off-site from his home. By 1861, he'd apparently advanced in the business because the census taker listed Caleb as a licensed victualler at a pub known as the White Hart. A decade later, he'd become publican of the Three Horseshoes in the same village and he kept that position until his death in 1885 at the age of 62. The records show that his two sons and two twin daughters each spent their childhood in either in a beerhouse or a pub. One of the twins was my great-grandmother Hannah North, who would later marry Joseph Wooster and start our Wooster line of publicans. The Aylesbury newspapers provide more robust details about life in the North household. At first glance, Caleb seemed to be well-respected, prosperous citizen of Towersey. He supported his community by donating to the Towersey school improvement fund when he managed the Three Horseshoes,17 and he was noted as a champion horse breeder who produced a "celebrated" sire known as Old Brown George.18A few of Caleb's transgressions appear in the papers, too. A court appearance in 1852 was for the charge of having in his possession "four unjust pints, a quart and a half-pint," meaning that he was allegedly serving his patrons undersized volumes of beer. Ann had also attempted to hide one of the small containers from the constable, so "to protect the public," the magistrates chose to "inflict the highest fine in their power" of £5.19 Caleb's penchant for serving beer during off-hours is also well-documented, starting with a charge of selling beer too early on a Sunday in 1856. The magistrates accused him of having pint-pots of beer on the taproom table and a chimney corner while three other men were in the premises a few minutes before noon. Caleb pled his innocence by claiming the men had arrived ten minutes after their chapel service ended, and he assumed the noon hour had already passed since his watch was wrong. His explanation and his first offender status led the magistrates to "deal leniently" with him and he was only fined £2.20 In 1869, while publican at the Three Horseshoes, Caleb was found guilty of "illegal trading in beer on a Sunday" but he was only cautioned for the violation.21 But just a few months later, he was charged with the same offence after the police constable entered the pub and found two men and a woman sitting with a pint of beer at 9am on a Sunday. Caleb's attorney claimed that the beer had, in fact, been drawn for another person who "went round the county collecting ducks" and Caleb had therefore served that person legally since he was a "traveler" in need of refreshment during off hours. The magistrates didn't believe the story and fined Caleb £1.22 Caleb and his second son William also occasionally ran foul of the law because of their excessive drinking. In 1870, they caused another Towersey beerhouse proprietor to be accused of permitting drunkenness on his premises when they refused to leave on a May evening at half-past nine. The incident started when the parish curate (who also served as constable because no one else wanted the position) investigated a parishioner's complaint at the house and heard "very profane language and quarreling." He went in and saw "William North and his father Caleb North who were both drunk [and] the son being riotous." The curate asked them to leave but they refused and "William North dared him to interfere between him and his father, and refused to allow his father to leave." The proprietor then asked them to leave, but they refused. After a five minute stand-off, the curate left them there drinking. A witness testified that he didn't know how much William had drank, but Caleb had consumed a quart. The remaining witnesses defended the Norths and the proprietor saying it wasn't as serious as the curate alleged. One said that he saw several men drinking from Caleb's quart and he had been offered some from it as well, and upon leaving, Caleb ordered a quart of beer for two men at the door. A final witness "swore that the Norths were quite sober." The court dismissed the case by giving only a caution to the proprietor, indicating that sympathies of both the magistrates and the witnesses were with the Norths and the proprietor, rather than with the less popular curate-constable.23 In July 1869, the previous constable found William and a "man named Wooster lying drunk on the road at Towersey, at half past twelve" on an early Sunday morning. The constable woke them up and walked them to their house. To quote the court record, William then "abused [the constable] and called for his father to come out, for there was a thief in the yard. He afterwards followed [the constable] down the road using bad and abusive language, and threatened to throw [the constable] into the pond. He also called on several of the bystanders to help him do it..." Caleb was called to testify on behalf of his son and claimed that the place where William was found was, in fact, on a public pathway on Caleb's premises. It wasn't a carriage road, he said, and so "there was no danger of his being run over by any carriage coming that way." The magistrates didn't accept the alibi and found William guilty, fining him 5s plus 15s for court costs. The drunken Wooster on scene was Daniel Wooster (I00949), Joseph's younger brother and my great-granduncle! He confessed to his involvement in the incident and was fined 5s plus 11s costs.24 Despite this incident, a few years later Dan will become a publican and we will review his unfortunate short career. A more serious incident that occurred involving the North family took place on a Monday night at half-past nine at the Three Horseshoes pub in August 1867. A customer came in with a loaded gun and placed it under a seat. According to the Bucks Herald, "The gun soon after exploded and shattered the foot of Martha North, daughter of Caleb North." The man "decamped to Thame, leaving the unfortunate girl weltering in her blood. Medical assistance was procured [and] it was deemed advisable to remove her to Aylesbury Infirmary, whither she was accordingly conveyed."25 At that time, Martha was 17 years old and was the twin sister of my great-grandmother Hannah, who would marry Joseph Wooster six years later. Martha survived her gunshot injury, married a horse proprietor named John Andrews, had seven children, and lived until 1931. The archives indicate that she never lived or worked in a pub again. That would not be true of her twin Hannah North. Despite his brushes with the law, Caleb kept his licence to operate the Three Horseshoes through 1883. Two years later, on February 2, 1885, his application for a licence to operate another pub called the New Inn was denied by the magistrates because they "were not being satisfied as to the character of the applicant." Two testimonials supporting Caleb were presented by his attorney, but "a written statement was also handed in showing that North had had disturbances on several occasions at his house in Towersey, and that the same was badly conducted."26 Only nine days later, Caleb died at the New Inn at the age of 61. His obituary notice identified him as being "for many years of the White Hart and Three Horseshoes Inns in Towersey."27 Joseph Caleb Wooster (1846-1924) - Longwick and Princes Risborough, Bucks Joseph Caleb Wooster was born the eighth child to prosperous Bucks farmer James Ives Wooster (I00521) and his wife Sarah Eggleton Wooster (I00522). Joseph grew up in the village of Ilmer four miles northwest of Princes Risborough, where his father farmed 157 acres and employed eight workers and a midwife. The family consisted of four daughters and eight sons with an age span of 22 years between them. The oldest Wooster sons were the first to leave when eldest John (I00523 - Nick Wooster's great-great grandfather!) married in 1857 and ultimately settled in Colne, Lancashire by 1880, while the next sons William (I02363) and Benjamin (I02364) migrated to Australia in the following years. By then, the remaining family began to show signs of stress after James Ives Wooster died in 1863, and deteriorating economic conditions compounded by excessive beer drinking were likely causes. In 1871, 58-year-old widow Sarah was the family head and continued to farm 119 acres, with four hired men and boys. At age 24, Joseph was the oldest remaining child in the household with his youngest sister Mary (I02648) and four younger brothers Dan (I00949), George (I02649) and Frank (I02650). Over the next two decades both beer consumption and beer sales became a Wooster tradition in this part of Bucks County. Ultimately five of James Ives and Sarah Wooster's twelve children would become publicans for at least a few years, a remarkable phenomenon for a single family at the time. Surprisingly, Sarah's daughters were the first in the family to become publicans. Oldest Ann Wooster (I02362) married James Kingham (I01085) in 1854 and the couple operated the White Horse pub two miles away in Longwick in the 1860s, while the next oldest daughter Sarah (I00945) married Henry West (I02943), a beer retailer and publican in the village of Chinnor, about five miles south of the family farm. Joseph's next oldest sister Frances (I00947), known as Fanny, married Thomas Goodchild (I02422) in 1865 and were publicans operating Longwick's Red Lion by 1871. These Wooster-born women would have long careers except for Ann and her husband who had given up the business and at some point before 1871, and were listed in subsequent censuses as a lacemaker and farm labourer for the rest of their lives.The Three Horseshoes at Towersey as it is today. (https://threehorseshoestowersey.co.uk/)

Stories published in the Aylesbury newspapers at the time reveal the extent of the hardships that widow Sarah faced keeping her youngest sons from an early demise. The pages are filled with transcripts from petty court sessions held across the county that described dozens of alcohol-induced offences in every hamlet, village and town. The Wooster boys were definitely not the only young persons appearing before the magistrates, but they did seem to be frequently called to defend their behaviors in Princes Risborough's court. The first known account appeared in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News on Saturday, 1 August 1868 with the ignominious headline "UNDUTIFUL SONS:" On Wednesday, at the Risborough petty session, (before the Rev. W. E. Partridge) Daniel, Joseph, Frank and George Wooster were brought up at the instance of their mother, Mrs. Sarah Wooster, who asked that they might be bound over to keep the peace. Mr. John Eggleton, parish constable [and very likely a relative of Sarah's], stated that on Sunday morning, the 26th ult., the defendants were quarrelling in their mother's house, and there was blood on them as if they had been fighting. They were each ordered to enter into their own recognisances in £10 to keep the peace for twelve months.28 Having previously pled guilty in 1869 to a drunkenness charge in nearby Towersey with his future sister-in-law's brother (William North), Dan Wooster narrowly missed being remanded to the authorities and fined £10. Then in 1870, one of these Wooster was brought up again on similar charges. Under the unambiguous heading of "DRUNK AND RIOTOUS," the Bucks newspaper published an account of how Joseph Wooster, Joseph Kingham, James Brown, William Brown, Ebenezer Brown and James Garden were charged with that offence in another petty session. The local police sergeant testified that on the 18th of April, the group was "fighting and swearing" at the Longwick village spring fair, "creating a great disturbance." Fortunately for Joseph and his compatriots, their case was postponed twice as the police witnesses were unable to appear before the magistrates, so the charges were dropped due to "contradictory evidence."29 The following year, at the age of 18, George Wooster, the second youngest son, immigrated to the United States to begin a successful life as a farmer, cotton gin owner and merchant in Georgia. Frank, the youngest in the family, also chose to escape to the U.S. and moved to Texas in 1880. Youngest daughter Mary married George East, a harness maker, and lived a long and quiet life in Monks Risborough. Unlike her three older sisters, she never lived in or operated a pub. In the 1870s, Sarah's remaining two sons. Joseph and Dan, followed their older sisters' lead and decided to enter the beer retailing and pub trade. After Joseph and Hannah married, one can assume that her knowledge gained growing up in her father's pubs had some influence upon his decision to try it. Since Joseph apparently had more experience drinking beer than selling it, her understanding of both the good and bad aspects almost certainly influenced their move from the family farm in Ilmer to Longwick in 1873 when they first went into the business. A notice in the newspaper announcing the birth of their first child Julia at the Sportsman's Arms that year is the first evidence that Joseph had been approved by the local magistrates to receive the necessary licence despite his previous drinking issues.30 The family lived there until 1876 when he acquired the rights to operate the Star pub on Church End in Princes Risborough. The 1881 census recorded the growing family still residing at the Star with Joseph having the combined occupation of farm labourer and beer retailer. Kelly's Directory included him as a beer retailer at the same location in 1883 and this would be the last published evidence I could find of Joseph's career as a publican. My grandmother Lillie was born in 1885, not in Princes Risborough, but instead in Joseph's home village of Ilmer that had no pubs or beerhouses at the time. Thus, my hope that she had been born in a pub was not true, though it's very likely that her first five siblings were.The Red Lion in Longwick, with rooms available. (https://pubshistory.com/Buckinghamshire/PrincesRisborough/RedLion.shtml)

Younger brother Dan Wooster also entered the business after he married Charlotte West in 1871. Like Hannah North, Charlotte had publicans in her immediate family. Her older brother Henry West (and his wife Sarah Wooster West, Dan's older sister) was the licence holder at the Pheasant in the hamlet of Red Lane in Oxfordshire's Chinnor at the time, and likely influenced the young couple to try the business in Longwick. At the age of only 27, Dan's career as a beerhouse operator ended tragically with his death in 1876, but Charlotte received his licence in a petty session transfer and carried on the business herself through the 1880s while she raised their three children, William, Albert and Ann.31 Longwick at the time had 326 residents that supported Charlotte's beerhouse and four local pubs -- the Sportsman's Arms, the White Horse, the Duke of Buckingham and the Red Lion, the latter of which was managed by her sister and brother-in-law Frances and Thomas Goodchild. Charlotte must have been a talented and popular beerhouse landlady to compete successfully with those presumably larger establishments. We can learn something of what her life was like from a newspaper account of an incident in November 1883 when a drunk customer threw a rock through her taproom window, hitting another patron in the side of his head, after she tried to remove the abusive man. The reporter describes her beerhouse as having "no sign to the house," meaning that it was not considered a pub.32 Charlotte remarried in 1886 and her second husband Frederick J. Rogers held the licence for their business until his death in 1902.33 From that point, Charlotte ran the pub known as the Three Pigeons in Longwick through 1915. None of Dan's children succeeded her in the business. Oldest son William Wooster (I311841) moved to London and became a chemist, and their younger son Albert (I312038) died of pneumonia in 1900 while serving as a lance corporal with the Army in Cape Town during the Boer War. Her younger daughter Charlotte Wooster Rogers and her husband Henry Rogers (as yet unidentified but possibly the son of Boaz Rogers of Monks Risborough?) carried on as the licensed victualler of the Three Pigeons through 1939. Charlotte West Wooster Rogers lived as an invalid there until her death in 1935, ending a remarkable beer selling career of over fifty years! That Wooster publican lineage didn't end there with the Longwick family. Chemist William Wooster's son Arthur Leonard Wooster (I312614), with his wife Hilda (I312643), had taken up his grandparents' profession by 1939, becoming the licensed victualler at the Queen's Head in Gillingham, Kent. Another interesting multi-generational publican story descends from Thomas Goodchild and Fanny Wooster's son Ebenezer Goodchild (I02424). He married Anne Keen (I02430) and had a son named Robert Thomas Goodchild (I03077) who was the publican for the Bird in Hand in Princes Risborough in the 1950s.34 Dorothy Wooster Brock (I307196) of Meadle, Monks Risborough, was his niece. I will always remember her for kindly inviting me to a full Sunday roast dinner during my trip in 1991, and introducing me to her elderly dad who, as a young boy, met my great-granduncle George Wooster during a visit back to England. Dorothy helped me start building my Wooster tree in those pre-Ancestry days and for that I'll always be grateful. Unlike Charlotte's, Joseph Wooster's career as a publican lasted only about eight years and ended in the 1880s as his life appears to have taken adverse turns. He was found guilty of assault on an old acquaintance from his childhood days outside of the Star in 1882 and was fined £10.35 The next year was the last time his name appeared in a commercial directory as a publican indicating that the incident probably ended his tenure as a licence holder. He is listed as a farm labourer in Ilmer with his family in both the 1891 and 1901 censuses, and in 1900 he was fined for truancy due to his failure to keep his youngest daughter Bertha (12 years) in school. We can assume hard times had befallen the family because in 1901, his next youngest daughters Rose (18 years) and Lillie (15 years) had each taken jobs as a domestic parlor maid and a general servant. The following year, Joseph and most of his remaining family in Ilmer accepted George Wooster's invitation to immigrate and start new lives in Georgia.36 No other offences can be found in the local records or newspapers there for the remaining two decades of Joseph's life. It seems plausible that his new environment in a "dry" state that prohibited all alcohol sales in 1907, and the family's adherence to the strict Primitive Baptist lifestyle they adopted may have prevented alcohol-related issues.37 He and Hannah enjoyed their final years farming in Meriwether County until George died in 1912, and then living in a quiet suburb of Atlanta called College Park, close to their daughters Rose and Bertha's families there, and Lillie's family in Haralson, Georgia.38The Sportsmans Arms was situated on Lower Icknield Way. This pub had become "The Sportsman's Garage & Motor Repairers" by 1931. Due to its prominent location at the Lower Icknield Way crossroads (the intersection of two drove roads), the pub was a popular drinking spot with rural workers. Now demolished with a petrol station now standing on the site.. (https://www.closedpubs.co.uk/buckinghamshire/longwick_sportsmansarms.html)

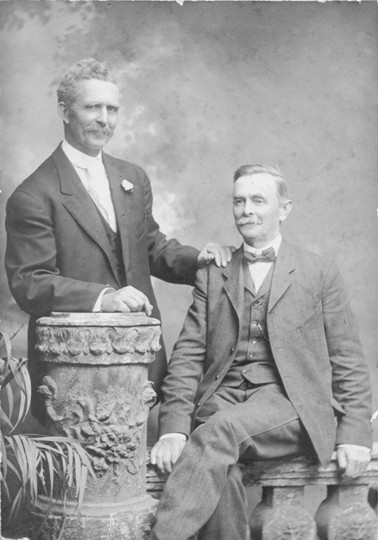

Joseph (left) and George (right) probably taken soon after Wooster family arrived in Georgia, ca. 1902 One thing is certain - my grandmother Lillie Wooster Miller spent the rest of her life in Georgia as a strong-willed opponent of alcohol and encouraged her children to do the same. The drink-induced troubles she saw among her older relatives may have given rise to her life-long animosity towards alcohol. A favorite family story passed down from World War II days is that when her veteran son Marvin came home for a visit while in the Army, he brought a flask of brandy into her house to share with his brothers. Lillie spotted the indiscretion and threw him out of the house, threatening to "box his ears" if he returned with the flask. Discovering these Wooster publican stories helps me to better understand this remembrance and the struggles that brought my ancestors to Georgia. In fact, these pub stories may have set the circumstances that caused me to be born in Georgia. I wish I could have known Joseph, Hannah, Lillie and all the others in person, but at least now I understand their lives much better. I want to believe, too, that my Wooster beer-selling forebearers in Bucks brought cheer into their neighbors' hard-working lives by welcoming them into their cozy (if a bit rowdy) pubs and beerhouses. I wouldn't want Lillie to know it, but a case of Newcastle Brown Ale contributed to the production of this article! More to come.... While compiling this research, I've discovered other publican stories for the following Woosters and hope to write their narratives in future newsletters about their lives in the profession:Seated, left to right - Joseph and Hannah Wooster, Rose Wooster Scraggs, Lillie Wooster Miller; Children, left to right - Rosie May Scraggs, Annie Maud Scraggs, Robert Scraggs, Alma Miller; Standing, left to right - Bertha Wooster, Humphrey Scraggs.

Arthur (I00004) and Edith Wooster (I00006) - publicans fondly remembered for their 38 years at the Bell in Stoke Mandeville and the Nag's Head in Aylesbury Clara (I03855) and William John Wooster (I02309) at the White Horse and Ardenne Arms, Hammersmith, London Catherine (I00017) and James Wooster (I00021) of the Plough Inn, Terrick near Ellesborough in 1911 Timothy Wooster (I00027), an early publican (1818-1828) at the same Plough Inn whose son Joseph Wooster (I00150) continued his career at the Crown and Scepter, Brushy, Herts Father Charles (I00442) and son Charles, Jr. (I00444) of the Red Cow in Wycombe in the 1850s through the 1880s Aaron Hill Wooster (I00860) of the Ballot Box, Horsenden Hill, Middlesex in the pre-World War II years Joseph Wooster, Jr.(I01698), proprietor of the Okaramio Tavern, in Kaituna Valley near Havelock, New Zealand in the World War I era. Notes and Sources 1. Because the Great Wooster Tree database proved so essential to this project, I've included the Person ID for all Woosters citied so that readers can more easily link them to their own family members. All census and directory information comes from the Ancestry.com website. If anyone needs data about a specific person or event cited in the article, please email me at mndawg1@charter.net and I'll be happy to send the source information. 2. Fowler, Simon, and Family History Partnership. 2009. Researching Brewery and Publican Ancestors Second ed. Bury: Family History Partnership. Accessible at https://archive.org/details/researchingbrewe0000fowl,10. 3. Alehouses and beerhouses could not sell wine or spirits. The definitive history of alehouses in pre-1700 England is: Hailwood, Mark. 2016. Alehouses and Good Fellowship in Early Modern England Paperback ed. Studies in Early Modern Cultural, Political and Social History, Volume 21. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. 4. Fowler, 6-11. 5. Ibid., 38-43. 6. Ibid., 6-11. 7. For a very detailed, long history of Licensing Acts, see https://pubshistory.com/LicensingActs.shtml. A useful history of public houses and sources for research is found at: https://pubshistory.com/index.shtml. 8. Ibid. Because King William IV was on the throne when Parliament passed the Beerhouse Act, he is the most popular monarch included in public house names. The most common modern pub name is the Red Lion. A good overview of sign names is found at https://britishheritage.com/history/british-pubs-names. 9. "Shoulder of Mutton" is my personal favorite "house sign." There were five operating with that name in Buckinghamshire when a special pub census was taken in 1872. Mr. Paul Evans of the Buckinghamshire Archives kindly provided a link to this very useful document titled Return of Public Houses and Beer Houses, 1872 that records the place, the year first licensed, the house sign name, the occupier/operator, the owner's name and address, and the leaseholder's name and address for 1,450 pubs and beerhouses in the county at the time. It can be downloaded from https://buckinghamshire.epexio.com/records/Q/RLv/21. The archives also has extensive licensing records on site in Aylesbury. Other informative websites that provide historic pub information are: https://pubshistory.com/ and https://www.closedpubs.co.uk/. 10. Fowler, 38-43. 11. Ibid., 42. 12. Ibid., 6-11. 13. Bucks Herald, 4 September 1869, 5. 14. Fowler, 8. 15. Fowler found similar patterns in his public house research. See Fowler, 9. 16. The Register of the Baptisms in the Parish of Towersey in the County of Bucks, 1813-1886 provides fathers' occupations in addition to baptismal data and parents' names. If available, these are essential sources for off-census year information. This parish book is available at Ancestry.com. Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1915 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. 17. Bucks Herald, 6 February 1875, 6. These local papers are accessible by subscription to the British Newspaper Archive at https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/. They can be difficult to read but provide exceptional details and colorful accounts of crimes and other drunken misdeeds at the village level. They also provide beerhouse and pub licensing information. 18. Cumberland and Westmorland Advertiser, and Penrith Literary Chronicle, 31 March 1874, 1; Bucks Herald, 28 March 1874, 1. 19. Bucks Chronicle and Bucks Gazette, 15 May 1852, 3. 20. Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, 3 May 1856, 5. 21. Bucks Herald, 4 September 1869, 5. 22. Bucks Herald, 24 July 1869, 5. 23. Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, 25 June 1870, 6. 24. Bucks Herald, 24 July 1869, 5. 25. Bucks Herald, 17 August 1867, 7. 26. Bucks Herald, 7 February 1885, 8. 27. Bucks Herald, 21 February 1885, 8. 28. Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, 1 August 1868, 8. 29. Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, 9 July 1870, 5. 30. Bucks Herald, 27 September 1873, 8. 31. Bucks Herald, 9 September 1876, 5. 32. Bucks Herald, 17 November 1883, 6. 33. Bucks Herald, 29 November 1902, 8. 34. The Bird in Hand is still in business and was named 2023 Pub of the Year by the Campaign for Real Ale for their commitment to sell original and local ales. See https://www.bucksfreepress.co.uk/news/23445626.princes-risboroughs-bird-hand-named-pub-year/ 35. Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, 16 December 1882, 8; Bucks Herald, 16 December 1882, 8. 36. Joseph came to the U.S. with his wife Hannah and youngest daughters Lillie and Bertha; his son Caleb Joseph and his wife Annie with their infants Caleb, Jr. and Florence; and his daughter Mary and her husband Thomas Baldwin. Joseph's other daughter Rose arrived in Georgia a few months later with her fiancé Humphrey Scraggs. Caleb and Mary's families returned to England by 1904. Family lore suggests that they either hated Georgia's brutal hot and humid climate or didn't like having their uncle George as their boss at his cotton gin. 37. Georgia banned the production, transportation and sales of all alcoholic beverages between 1907 and 1935 exceeding the national prohibition period of 1920-1933. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/prohibition-in-georgia/. Illegally made whiskey known as "moonshine" was readily available from bootleggers in many rural areas including Meriwether County where Joseph and George Wooster lived in the 1910s. 38. College Park is adjacent today to Atlanta's behemoth Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. Joseph and Hannah Wooster are buried in the town cemetery.Table of Wooster Pubs, including links to photos and histories.Map of Wooster pub locations in Bucks

Page last updated

04 July 2025